Back

Blog

Resilient Cities Require Resilient Food Systems

Kim Zeuli, ICIC, and Ryan Whalen, The Rockefeller Foundation

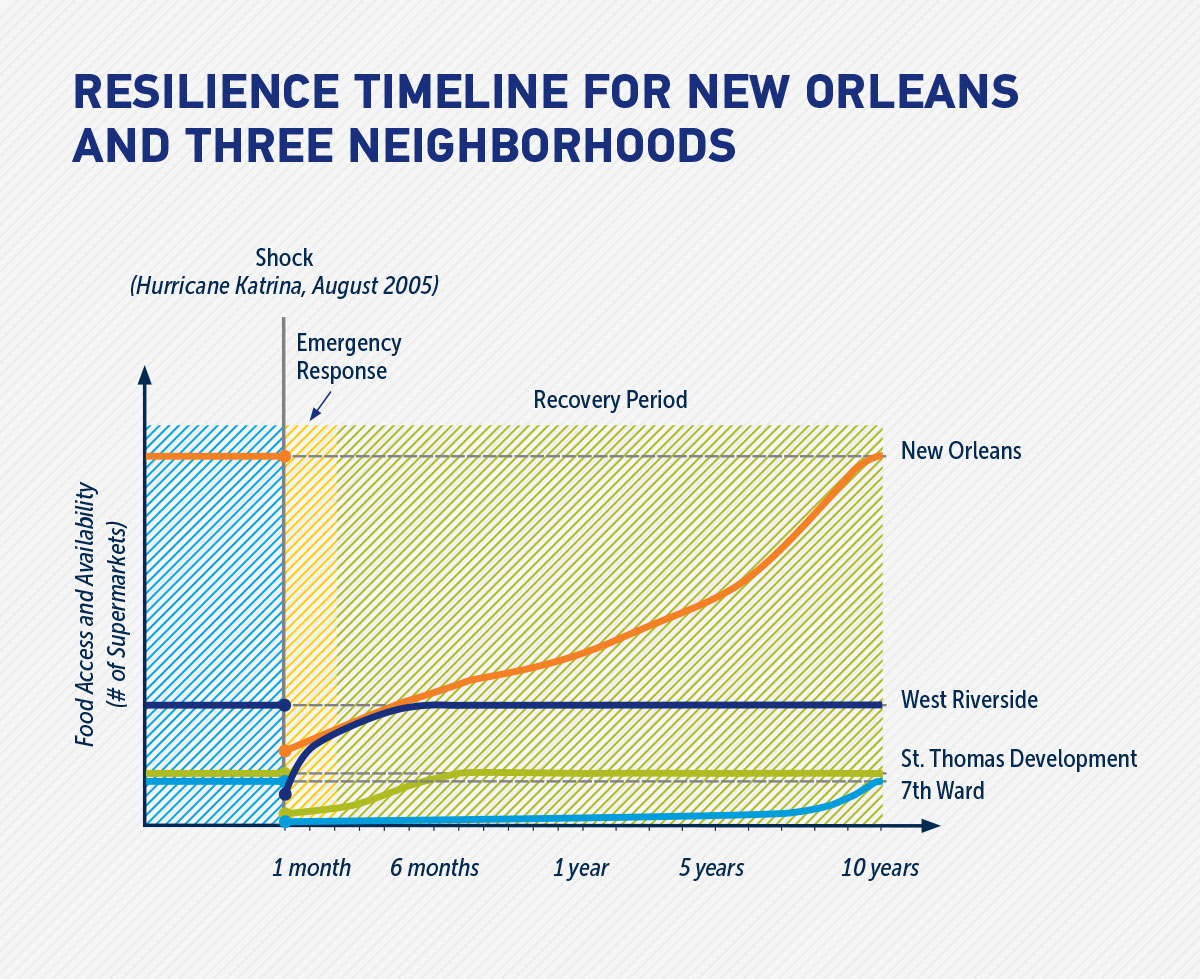

City leaders are prioritizing resilience planning to better prepare for severe natural disasters such as earthquakes, hurricanes and superstorms. Food systems, however, have been largely overlooked in these planning efforts. Most cities expect to provide residents with food for a relatively short period of time—a few weeks at most—during the immediate aftermath of a natural disaster. But as Hurricane Katrina demonstrated in New Orleans, food system disruptions may last months or years and vary by neighborhood. Such long-lasting disruptions can create significant food access issues, especially for populations that are already food insecure.

100 Resilient Cities (100RC), pioneered by The Rockefeller Foundation, helps cities around the world become more resilient to the physical, social, and economic challenges that are a growing part of the 21st century. 100RC views resilience not just as shocks—earthquakes, fires, floods, etc.—but also as stresses that weaken the fabric of a city on a day-to-day or cyclical basis. New research from the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City (ICIC), supported by a grant from The Rockefeller Foundation, strongly suggests that city leaders should bring food systems to the forefront of discussions and planning around urban resilience.

The Resilience of America’s Urban Food Systems: Evidence from Five Cities provides a compelling look at the vulnerability of urban food systems to natural disasters in Los Angeles, New Orleans and New York City. ICIC’s analysis assumed a hypothetical 7.8 magnitude earthquake in Los Angeles, while looking at the actual impact of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and Superstorm Sandy in New York City.

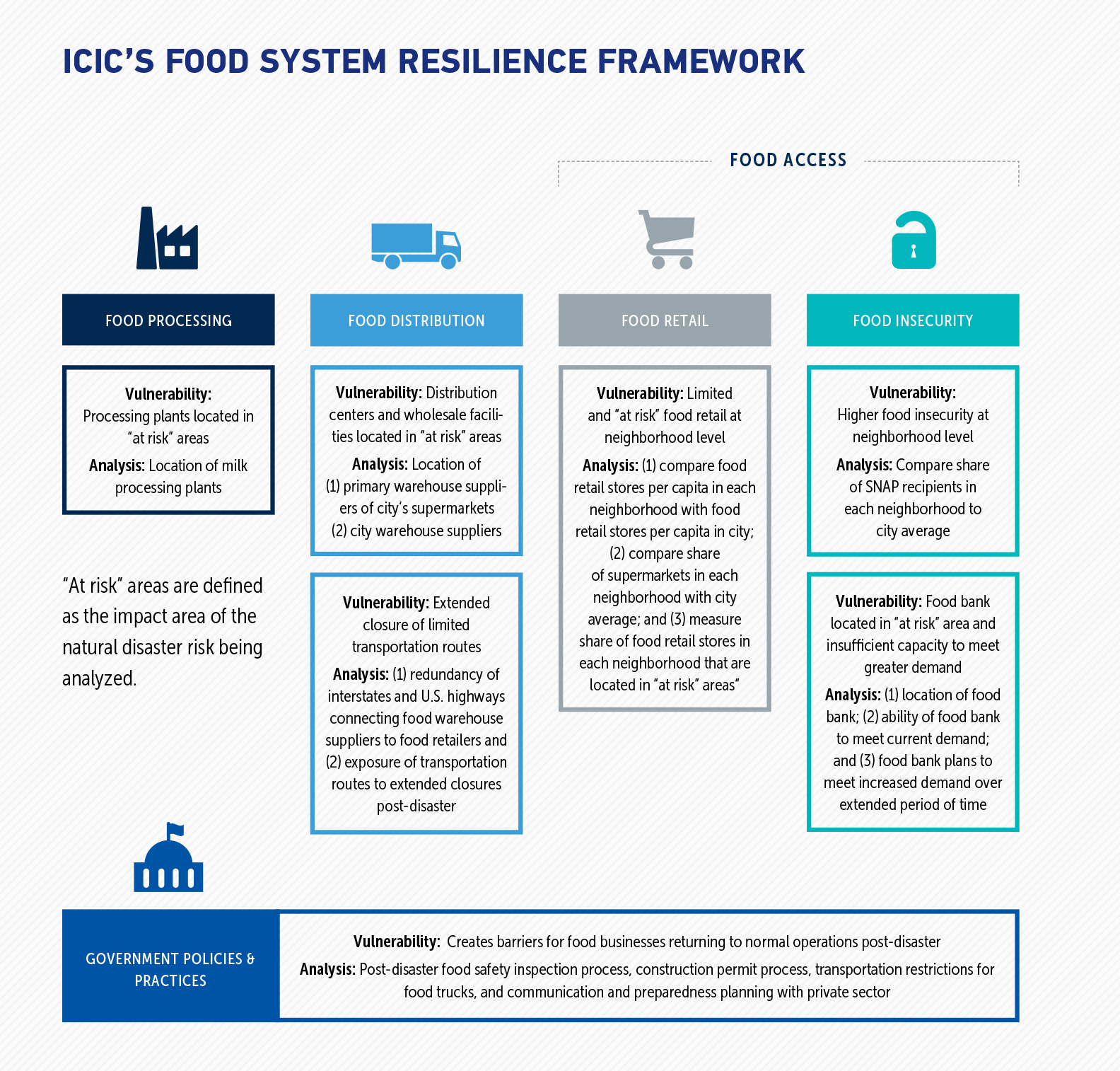

An Urban Food System Resilience Framework

Considering the aspects of food systems that city leaders could realistically address (therefore not including food production), ICIC developed a unique framework that allows cities to identify and assess the resilience of their food systems to different types of disasters. It analyzes vulnerabilities at the neighborhood level to identify specific areas (and populations) within the city that would be disproportionately impacted by food system disruptions.

Urban Food System Vulnerabilities

The comparative analysis of food systems in Los Angeles, New Orleans and New York City finds both shared vulnerabilities and unique weaknesses that are a function of differences in each city’s food system and their exposure to different natural disaster risks.

None of the cities were exposed to significant food processing vulnerabilities. Because of the global nature of the food system, a very small share of total food consumed in a city is processed and packaged locally. For example, if a major earthquake hit Los Angeles, some food processing plants would likely be damaged, but they are largely food exporters. The food consumed in Los Angeles, as is the case in most cities, is sourced from food processing plants across the country and world.

All three cities face food distribution vulnerabilities because of the location of some warehouse supplier facilities in “at risk” areas. Los Angeles faces the greatest risk, with the vast majority of its warehouse suppliers subject to earthquake damage. In New Orleans and New York City, only local warehouse suppliers are at risk, creating greater risks for smaller grocery and corner stores, which rely more on local warehouse suppliers for their food supplies.

Fresh food distribution markets concentrate many wholesalers in a single location, creating significant vulnerability if the market is located in an “at risk” area. Hunts Point, New York City’s fresh food distribution market, highlights the unique vulnerabilities associated with this type of market. Hunts Point poses the greatest single food distribution vulnerability for New York City because of the concentration of wholesalers in a single location, its relative importance to the city’s food retailers, and its location. A recent study finds that 25 percent of produce, 35 percent of meat, 45 percent of seafood, and 12 percent of all food distributed within the city moves through Hunts Point, which is located on 329 acres on a peninsula in the Bronx, making it vulnerable to flooding from storm surges.

All three cities have transportation routes vulnerable to extended closures in the aftermath of a disaster, creating potential supply chain disruptions. Both New York City and New Orleans are surrounded by water, funneling food distribution trucks onto bridges and tunnels, some of which are inherently prone to flooding because of their proximity to water. In Los Angeles, most of the transportation routes into the city would be impacted by the earthquake scenario that was analyzed.

For every city, food availability in some neighborhoods will be disproportionately impacted by a natural disaster. The greatest disparities in food availability still exist in New Orleans, but all three cities have some neighborhoods with food access vulnerabilities:

- New York City had the fewest—slightly less than two percent of all neighborhoods. Yet, after Sandy, some local grocery and corner stores in Staten Island and in the Rockaways were closed for an extended period of time—in some cases months or over one year.

- In Los Angeles, 17 percent of all neighborhoods have food access vulnerabilities. One of the neighborhoods has no food retail stores.

- In New Orleans, a quarter of all neighborhoods have food access vulnerabilities. Twelve of the neighborhoods have no food retail stores.

We learn from Katrina and Sandy that delayed or inadequate insurance and government assistance payments can hold up the reopening of smaller grocery and corner stores, adding another layer of food availability vulnerability in these neighborhoods. In addition, food banks in all three cities are located in “at risk” areas and would also face challenges meeting increased demand for an extended period of time.

Creating Resilient Urban Food Systems

The report offers five recommendations that serve as a playbook for city leaders to strengthen the resilience of their urban food systems and shorten the recovery window needed to return food systems to their normal state. While a strong local government role is essential, the recommendations reflect the fact that strengthening urban food system resilience requires leadership from both the public and private sectors.

- Conduct a food system resilience assessment: As this study shows, every city will have unique food system vulnerabilities and an assessment of the entire food system is needed to inform resilience plans. Urban food systems remain largely unstudied and there is a lack of data on the origin of food, distribution paths and food retail. Boston, Los Angeles and New York City stand out as cities that have already started to analyze the resilience of their food systems.

- Incorporate food systems into resilience planning initiatives and prioritize resilience on urban food agendas: Most cities overlook food systems in their resilience plans. Likewise, most urban food agendas do not currently prioritize resilience planning. Food system resilience should be a priority for city food agencies, food policy councils, and the U.S. Conference of Mayors Food Policy Task Force. There are approximately 200 food policy councils in the U.S., which are designed to influence local and state food policy and typically include representatives from across the food system. Food policy councils would create an efficient platform to advance food system resilience policies and initiatives.

- Develop neighborhood food resilience plans: Planning should be prioritized for neighborhoods where food access would be disproportionately impacted by a natural disaster. In the long-term, food insecurity and a lack of food retail stores will need to be addressed. In the short-term, the resilience of food banks, the backbone of food safety nets, should be strengthened.

- Strengthen food business resilience: Many smaller food businesses are likely to be underprepared for business disruptions. Cities should work with the food industry to ensure all food businesses have adequate insurance coverage and business continuity plans in place to ensure that they fully cover a wide range of potential disruptions. City leaders should leverage the expertise of large organizations to share best practices with other food businesses and to improve the logistics of food provisions in the aftermath of a disaster.

- Develop government policies and practices that help food businesses quickly return to normal operations: Three government policies are critical for food business recovery—food safety inspections, the construction permit process, and transportation restrictions. Government agencies should develop a protocol for streamlining inspections and permitting, policies that eliminate restrictions on food business transportation, and a process for effectively communicating with all food businesses.

A Call to Action

Climate change will only increase the occurrence and severity of natural disasters in U.S. cities, and city leaders need to be prepared to respond. City leaders may assume that resilience planning for the city’s infrastructure in general is sufficient, since food distribution and retail depend on transportation and utilities. While resilient transportation networks and utilities are critical components of a resilient food system, they are not the only parts that matter. In addition, having a food system perspective in resilience planning will prioritize the most critical infrastructure investments to strengthen food distribution and food retail.

Cities that intentionally develop resilient food systems will ensure that food supplies return to pre-disaster levels as quickly and as equitably as possible, so that all residents have adequate access to food in their neighborhoods.

Learn more by reading the full report, The Resilience of America’s Urban Food Systems: Evidence from Five Cities.