Back

Blog

Inclusive Prosperity Is Incredibly Rare

This blog originally appeared in CityLab on May 25, 2017

Written by Richard Florida

Just a handful of large metro areas have been able to spread economic gains across all classes and races. What’s their secret?

America may be prosperous but it is not inclusive. On the one hand, the nation and its cities and metro areas are still recovering from the economic trauma of the Great Recession: Economic output is up and unemployment is down. But on the other hand, the gains from that economic recovery are disproportionately concentrated among a relatively small number of advantaged groups and advantaged places. Inclusive prosperity has proven distressingly elusive; wide swaths of cities and metros and large groups of people have missed out on the economic rebound.

The most recent edition of the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program’s Metro Monitor report for 2017 (and a blog post based on it)documents this troubling trend, tracking economic growth, prosperity and inclusion for America’s 100 largest metros areas over the post-recession, recovery period from 2010 to 2015.

There’s good news to report: Unemployment has fallen nationwide, and every single one of the 100 largest metros has added jobs and output. Not surprisingly, the strongest growth has been concentrated in knowledge and tech hubs metros such as San Jose (Silicon Valley), San Francisco, Austin, Seattle, Raleigh, Denver, Provo, and Nashville. Sun Belt metros like Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and Orlando also swelled, while Rust Belt metros continued to lag. San Jose’s economic output grew by a whopping 36 percent over this period; while Houston’s grew by 28 percent, reflecting the rise of the twin pillars of what I have dubbed America’s knowledge-energy economy, though the energy pillar has fallen off considerably since then.

But median wages increased in a little over half (53) of the 100 largest metros, and just 45 saw gains on Brookings’ overall measure of economic prosperity—a trifecta of productivity, averages wages, and living standards. Interestingly, Pittsburgh and Toledo ranked in the top ten: The Steel City enjoyed larger-than-expected job growth in construction, computer systems, and healthcare, while Toledo saw larger than triple its expected job growth in motor vehicle and parts manufacturing. They rank alongside knowledge hubs such as San Jose, San Francisco, Madison, and Nashville as well as energy centers such as Houston, Oklahoma City, Tulsa, and San Antonio. Tech hubs posted the strongest overall wage growth.

Far more distressing is how very few metros have registered any improvement in inclusive prosperity across races and classes (based on educational attainment), which the report measures as change in the median wage, change in the employment rate, and change in the relative poverty rate.

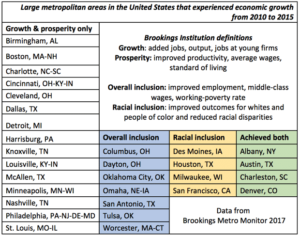

Only 30 of the 100 largest metro areas experienced increases in growth and prosperity from 2010 to 2015 and even fewer experience increased overall and racial inclusion. (Data from the Brookings Institution’s Metro Monitor)

Less than 15 percent (14 of the 100 largest metro areas) outperformed the average of their peers on composite scores for growth, prosperity, and inclusion, largely knowledge hubs and energy centers, though Detroit also made this group. Just 11 of America’s 100 largest metros saw gains in 9 core measures of the Brooking’s measures of economic growth, prosperity, and inclusion. Eight metros registered gains in inclusive economic prosperity for both white people and people of color, and only four metros—Austin, Denver, Charleston, and Albany—experienced inclusive prosperity in its truest sense, that extends to all races and classes. Those metros saw their median income earnings gap between white people and people of color decline. Even though Albany ranked lower in terms of economic growth and productivity, it managed to make improvements for racial inclusion, increasing median income and employment for both groups.

In addition to those 4 metro areas, another 7 of the 100 largest metros—Columbus, Dayton, Oklahoma City, Omaha, San Antonio, Tulsa, and Worcester—improved their employment rate, median earnings, and relative poverty rate, but those gains largely went more to white households rather than people of color. Median incomes for white people increased in these places, while the median incomes for people of color flat-lined. Four metro areas—San Francisco, Houston, Des Moines, and Milwaukee—saw improvements on racial disparity, increasing median income and employment rates for everyone. But these metros also saw an increase in their overall relative income poverty rates, where the ratio of people whose income falls below the poverty line increased.

These findings are consistent with other research by the Economic Innovation Group that found that just 9 of America’s 100 largest cities had high levels of prosperity along with low levels of spatial inequality, in mostly smaller sprawling places such as Scottsdale, Arizona, and Plano, Texas, or a college town such as Madison, Wisconsin, which are already affluent and homogenous to begin with. Tech hubs such as San Francisco and San Jose have high levels of both prosperity and inequality, while superstar cities such as New York, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and Boston have high inequality but more modest levels of prosperity, considering their size.

Although true inclusive prosperity is rare across America’s metros, there are two features of metros that seem to help shape it, according to the Brookings analysis. On the one hand, prosperity is more likely in innovative, high-productivity, growing metro economies based on technology, knowledge or advanced manufacturing. But on the other hand, it also stems from creating a robust middle strata of jobs and avoiding the economic bifurcation that is part and parcel of the new urban crisis faced by so many more metros. Albany, for example, saw huge job growth in semiconductor and electronic manufacturing (a 480 percent increase)—alongside jobs at colleges and schools and service jobs in personal care, construction, and grocery stores.

In general, this robust middle seems to come from three sources: more higher paying, mid-skill jobs in so-called advanced traded sectors, more higher paying mid-skill jobs in “non-traded” sectors like construction and logistics, and better paying, low-skill local service jobs in sectors like retail and hospitality.

A high-road path to inclusive prosperity is possible, but only if we rebuild the middle of our economy.