Back

Blog

How Resilient Were Small Businesses during the First Year of the Coronavirus Pandemic?

A look at what happened to established business owners and lessons for the next crisis

by Howard Wial, Senior Vice President and Director of Research, Initiative for a Competitive Inner City, and Devon Yee, Senior Research Analyst, Initiative for a Competitive Inner City

December 2021

During the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic, many small businesses’ prospects for survival seemed dire. In a widely-cited June 2020 paper, University of California-Santa Cruz economist Robert Fairlie used the Current Population Survey (CPS) to show that the number of active business owners fell by 22 percent from February 2020 to April 2020, the largest drop recorded since the CPS began in the 1940s. But research covering the later months of 2020 tells a more optimistic story about what happened to small businesses during the pandemic. For example, Bureau of Labor Statistics economists found business closures roughly back on their pre-pandemic track by late 2020. There is also evidence that business startups surged above their pre-pandemic rates by the end of that year.

None of the research published to date looks at what happened to the people who owned businesses before the pandemic began. How many went out of business during the pandemic? What did those who went out of business do? How did those who stayed in business cope with the crisis? If you’re a business owner or a small business assistance provider or policymaker, you’ll want to know the answers to these questions, not just for what they say about the coronavirus crisis but also because they can help you prepare for the next crisis.

We answer these questions by using the CPS to track the people who were active business owners in February 2020 over the next two months (until April 2020) and over the following year (until February 2021).[1] Surprisingly, no one has done this yet. (Fairlie’s work, widely reported in the news media as being about business “closures,” compares the total number business owners in each month, regardless of whe#_edn1ther they were in business before the pandemic or started businesses during the pandemic.) To make sure that we’re looking at business owners who devoted real effort to their business before the pandemic, rather than those who just operated businesses as a small side activity while working at another job, we consider only owners who worked at least 15 hours per week at their business or at least two days during the week of the survey in February 2021, just as Fairlie did.

41 Percent of Businesses Closed Between February 2020 and February 2021

Of the business owners who actively operated businesses in February 2020, 41 percent were no longer actively in business (i.e., they were working for someone else in a wage or salary job, not working for pay, or operating their business for less than 15 hours per week) in February 2021. This means that 41 percent of the businesses that existed just before the pandemic, a total of 5.3 million businesses, closed within a year.

Is that a large number of closures? Or was similar to what happened in non-pandemic years? After all, small business closures are common even during “normal” times. (According to the Small Business Administration, 7-9 percent of businesses with employees close and 30 percent of those without employees close every year, while half of business with employees close after five years.)

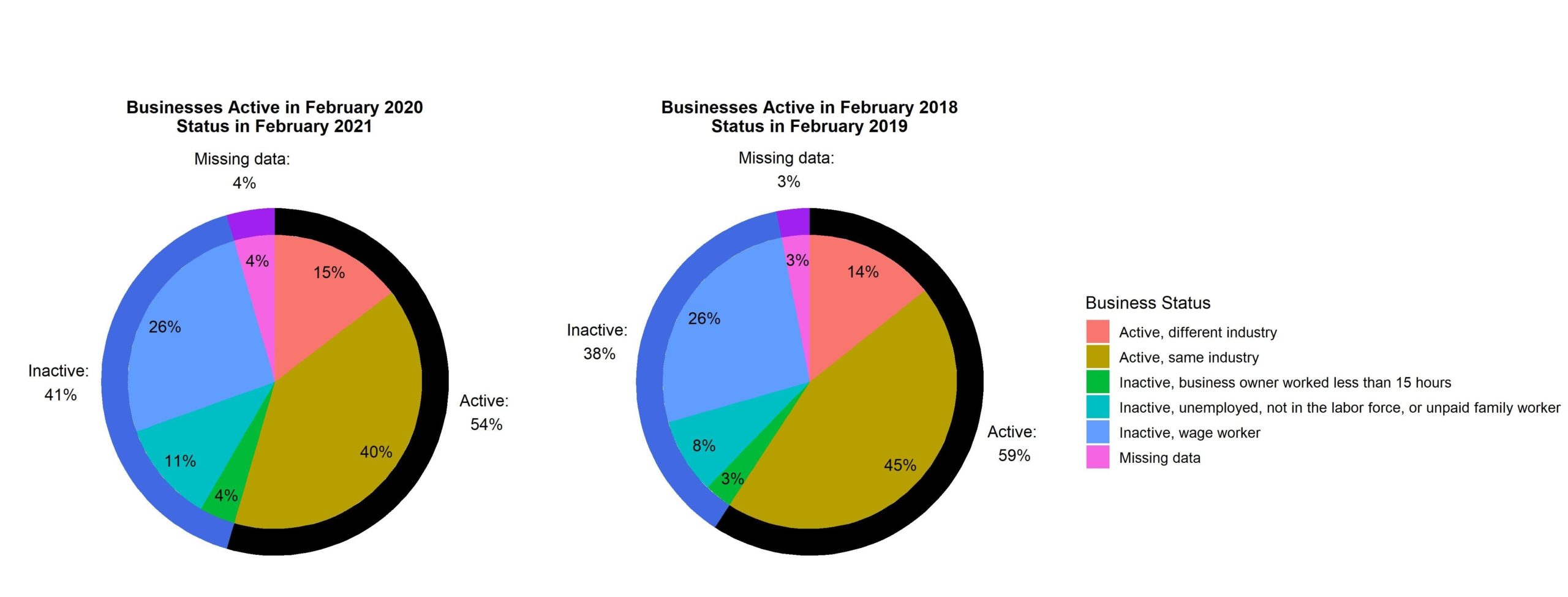

To estimate how many business closures between February 2020 and February 2021 resulted from the pandemic and the economic and public policy responses to it rather than from normal seasonal and annual changes in business activity, let’s compare our finding with what happened from February 2018-February 2019, long before the current pandemic began. During that non-pandemic year, 38 percent of businesses that existed in February 2018 closed by the following February (shown as “inactive” in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Business Closures from February 2020-February 2021 Compared with February 2018-February 2019

Note: Percentages within “active” and “inactive” categories may not sum to category totals due to rounding. Source: ICIC analysis of Current Population Survey data.

Although the difference between the 41 percent of businesses that closed during the first year of the pandemic and the 38 percent that closed during our non-pandemic year is statistically significant, it isn’t huge. Does this mean that all the public concern about small business closures and the public policies meant to keep small businesses open were unnecessary? Far from it, as we’ll see when we look at what happened during the first two months of the pandemic.

23 Percent of Businesses Closed Between February and April 2020, More Than Half of the Number That Closed During the Entire First Year of the Pandemic

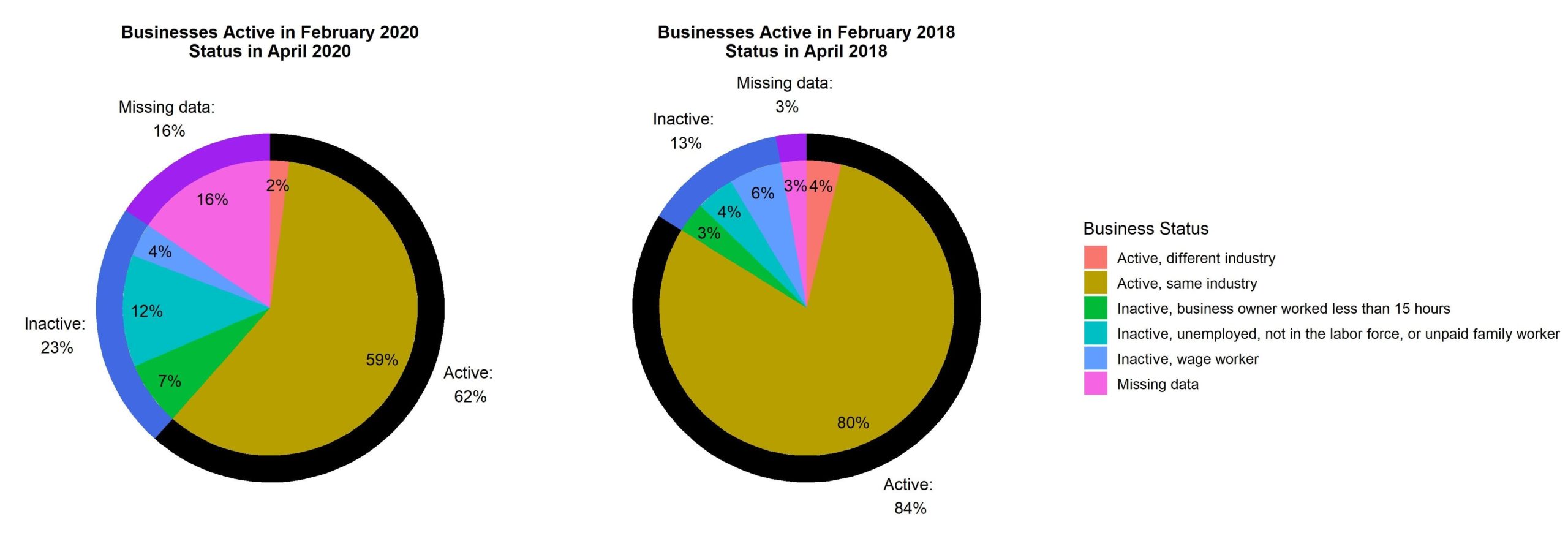

Of the businesses that existed in February 2020, 23 percent (a total of 3 million businesses) closed by April of that year (Figure 2). This is very similar to Fairlie’s estimate of 22 percent of businesses that closed during that period. To put this in perspective, the number of businesses that closed in the first two months of the pandemic is more than half the number that closed during the first year of the pandemic, although some of the businesses that closed in the first two months may have reopened later in the year.

Figure 2. Business Closures from February-April 2020 Compared with February-April 2018

Note: Percentages within “active” and “inactive” categories may not sum to category totals due to rounding. Source: ICIC analysis of Current Population Survey data.

In contrast, only 13 percent of the businesses that were active in February 2018 were out of business in April 2018. That’s just over a third of all the businesses that existed in February 2018 and closed within a year.

This tells us the pain that the coronavirus pandemic caused for business owners (and their employees and customers) was heavily concentrated in the early months of the pandemic. The American public and government policymakers were right to worry about and try to prevent business closures during that time.

How Businesses Adjusted: Making Hand Sanitizer?

Entrepreneurs who remained in business during the pandemic often found innovative ways to operate. Some changed their business models; many restaurants moved to takeout or outdoor dining. Some changed their products, even going into entirely new industries. During the first few months of the pandemic, the news media highlighted whiskey distillers who pivoted to making hand sanitizer. ICIC’s 2021 impact report tells many other stories of resourceful business owners who were able to survive and even thrive during the crisis by retooling their approach and offerings.

Our data don’t reveal all the ways businesses adapted but they do say how many shifted to a different industry (which, in our data, means a major shift, such as moving from whiskey to hand sanitizer). Table 1 shows that 15 percent of businesses that were active in February 2020 had moved to a different industry a year later, not much different from the 14 percent that did so between February 2018 and February 2019. Figure 2 shows that pivoting to a different industry was actually less common from February to April 2020 (when 2 percent of businesses did so) than during the same period in 2018 (when 4 percent did so). Industry-changing may have declined in the early months of the coronavirus crisis (compared to our non-pandemic year) because it takes time for a business to switch to an entirely new type of product. In any event, industry-pivoting demonstrated business owners’ resourcefulness but it wasn’t any more common during the first year of the pandemic than it was in an “ordinary” year.

Leaving the Business: Working, Not Working, or Cutting Back on Hours

Among those who stopped being active business owners, the largest number went to work for someone else. About 26 percent of all the people who were in business in February 2020 (more than two thirds of the active business owners who ceased being active owners) had jobs as wage or salary workers a year later (Figure 1). Among those who were in business in February 2018, an identical 26 percent were wage or salary workers the following February. In the first two months of the pandemic, 4 percent of business owners switched from being self-employed to working for someone else; while in our non-pandemic year, 6 percent of business owners switched. The decline in the share of business owners who got other jobs during the early months of the coronavirus crisis was probably due to the fact that there were fewer jobs to be had; in April 2020, the unemployment rate reached a seasonally adjusted 14.8 percent, the highest on record since the CPS began in the 1940s. By February 2021, when the unemployment rate had fallen to a seasonally adjusted 6.2 percent, it’s not surprising that more of the former business owners were able to get jobs.

The next most common outcome for business owners who stopped being active was not working for pay (becoming unemployed, leaving the labor force—not working and not looking for a job, or becoming an unpaid family worker—which includes working in a family business without a salary). Unsurprisingly, not working for pay was more common during the pandemic than during our non-pandemic year. In February 2021, 11 percent of pre-pandemic business owners didn’t work for pay, up from 8 percent during the same time period in our non-pandemic year. In the first two months of the pandemic, the percentage of pre-pandemic business owners was even higher—12 percent—up from just 4 percent during the same months of our non-pandemic year.

The least common outcome among business owners who stopped being active, but one that became more common in the early months of the crisis, was to reduce the number of hours spent working in their business below 15 hours per week, which generally meant no longer actively running the business or running it at a very low level. Of those who were active as business owners in February 2020, 4 percent spent less than 15 hours per week operating the business a year later, virtually the same percentage that did so in our non-pandemic year. But 7 percent of these same owners went below 15 hours per week in April 2020, more than double the 3 percent of February 2018 business owners who did so in April 2018.

Lessons for the Next Crisis

Support for businesses, both direct and indirect (via support for consumers and workers) is especially important during the first few months of a crisis such as the coronavirus pandemic. That’s when the pandemic and its associated public policy and consumer responses (such as mandatory shutdowns or health-related restrictions on some types of businesses and consumers’ reluctance to patronize others) exacted their heaviest toll.

During the early months of the coronavirus crisis, programs such as the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and expanded Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL) for businesses, and Economic Impact Payments and expanded unemployment benefits for individuals mitigated the damage to businesses. But the early response was insufficient to prevent the large rise in business closures that occurred in the early stage of the crisis. Support in the early months of the next crisis needs to be more generous and easier to access than it was during the coronavirus pandemic and direct support for businesses needs to be timelier.

BIPOC business owners suffered especially severe losses during the early pandemic. (Although our data didn’t include enough BIPOC owners to enable us to track them over the course of the pandemic, Fairlie showed that the numbers of Black-owned and Latinx-owned businesses fell by much higher percentages than the total number of businesses during the first two months of the pandemic.) PPP loans took longer to reach businesses in BIPOC neighborhoods than those in majority-white neighborhoods.

Although the Small Business Administration (SBA) disbursed $792 billion in PPP loans, this assistance was not prompt and was distributed through banks in the program’s first two rounds. Businesses that lacked pre-existing relationships with banks had difficulty obtaining loans. Since businesses owned by people of color often have weaker banking relationships than white-owned businesses, channeling assistance through banks made it harder for them to get loans. Minority business owners were underrepresented in loan awards in the first round, though this was not true later on in the program. Even among firms with good credit, firms owned by people of color had more difficulty meeting their financing needs than their white peers. According to a Board report by the Federal Reserve Banks, 13 percent of Black-owned businesses received all the financing they sought six months after the pandemic, 20 percent of Latinx-owned firms and 30 percent of Asian-owned businesses received all of the financing that they applied for, compared to 40 percent of white-owned businesses.

Direct support for businesses in the early stages of a crisis shouldn’t come with these built-in biases against BIPOC-owned businesses. Rather than rely on banks to distribute aid to businesses, a federal agency such as the SBA should provide funding directly to all businesses that qualify for it. If that isn’t possible, then business relief programs should be designed so that alternative lenders, such as credit unions and community development financial institutions, receive substantial amounts of funding to distribute to the (often BIPOC-owned) businesses they serve.

Assistance to businesses in future crises should also avoid other features of the PPP that created stumbling blocks for business owners. Federally funded grants are less cumbersome for businesses and less costly to administer than the PPP’s forgivable loans. At least one business owner decided not to apply for PPP loans and instead closed their businesses because they couldn’t be sure from the outset that the loans would be forgiven. Funding should also be flexible and accessible. Business owners in high-rent areas reported that the PPP’s requirement that 75 percent of funding be spent on wages and salaries was a barrier to their use of the program. (Lawmakers later changed this requirement to 60 percent.) Some business owners cited a lack of accessible language assistance as an obstacle to accessing PPP support.

Although the most severe impact of the coronavirus pandemic occurred in its first few months, business closures were still higher than “normal” even after a year. And that’s just the overall impact on closures. Rates of business closure may remain high for some types of businesses even as they approach non-pandemic levels overall. Even businesses that didn’t close in the early stages of the coronavirus crisis may still be suffering from depressed revenue. According to the most recent Census Small Business Pulse Survey (November 11, 2021, to November 28, 2021), 36 percent of small businesses expect that it will take more than 6 months to return to their normal levels of operations.) As we consider how best to support small businesses at the onset of a future crisis, let’s not forget that there’s still more work to do to help them become and remain resilient in this one.